Auto racing is hardly one of the greenest sports out there. But

Porsche has now come up with a racecar outfitted with a hybrid engine. The

technology could ultimately find its way onto the street.

The word is one that stands for the loftiest hopes of progress

in modern automobile engineering. It should come as no surprise that the

technology now graces even racecars.

"Hybrid" is printed proudly on the protruding rear

fenders of the new orange and white racecar made by sports car manufacturer

Porsche. The vehicle will compete in the 24-hour race at Germany's Nürburgring

track in May and "bring a new type of engineering to the racetrack,"

says Porsche's Executive Vice President for Research and Development Wolfgang

Dürheimer.

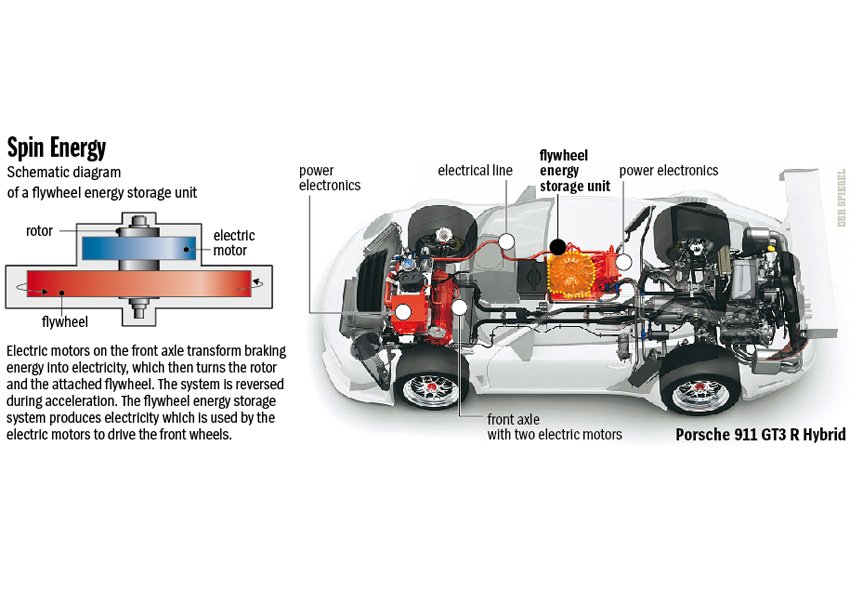

The Porsche 911 GT3 R Hybrid draws on two power sources. A

traditional six-cylinder engine at the rear of the vehicle provides 480

horsepower and drives the rear wheels. Two additional electric motors up front

can supply each of the front wheels with a short-term burst of 80 horsepower

during acceleration.

It can't be said for certain, though, that this accumulation

of power will automatically increase the car's odds of winning a race. The

electric components also make the car heavier, a serious disadvantage in auto

racing. Whatever gains the hybrid system achieves in terms of power, it must

also work to compensate for that additional weight.

Slight Resemblance to a Pressure Cooker

In addition, auto racing hardly affords the right working

conditions for hybrid technology. A hybrid vehicle's trump card, physically

speaking, is its ability to convert braking energy into electricity, and that

works best with slow deceleration. Racing, on the other hand, is a constant

interplay between full throttle and full braking. No battery can stand up to

that rhythm.

As such, Porsche's hybrid system isn't based on a chemical

storage system for electricity. Instead of a conventional rechargeable battery,

the car's designers included an energy recovery system that works mechanically.

The device sits on the usually empty passenger's side of the racecar, bears a

slight resemblance to a pressure cooker, and together with all its wiring and

electronics weighs a good 100 kilograms (220 pounds).

The unit is essentially an electric engine with a rotor and

flywheel that can accelerate up to 40,000 revolutions per minute. To access

this kinetic energy again, the device only needs to reverse its polarity and

become a generator. The energy stored in the flywheel is converted back to

electricity and flows to the electric engines on the front axle.

This "Kinetic Energy Recovery System" (KERS)

appears to be perfect for racecars. The flywheel unit charges within seconds,

meaning it can capture most of the energy created even by full application of

the brakes -- and make that energy available again just as quickly. One charge

of the system is enough to provide a 160 horsepower boost lasting six to eight

seconds.

Possible Street Application

Such a system would never be able to power a fully hybrid

vehicle for long distances with electricity alone. But it doesn't need to,

Dürheimer says. He sees a possible street application for this technology more

in sports cars, which could be made faster or more efficient. At the moment,

however, such a device is still much too expensive.

KERS originated in motor sports' most prestigious discipline

-- Formula 1 racing. Several racing teams adopted the technology for a single

racing season, before abandoning it in order to reduce development costs.

Now the system is coming in handy for Porsche, as the

company strives to create a new profile for itself in the sector that once made

the small-scale car manufacturer from Stuttgart into one of the guiding lights

of German auto racing glory.

In more recent days, however, the more Porsche grew, the

less involvement it had in the world of racing. The company hardly takes part

anymore in large, internationally renowned events.

Wendelin Wiedeking, known for restructuring Porsche during

his many years as CEO, was no fan of costly measures meant only to maintain the

company's mystique. His racing ambitions ran more along the lines of making

Porsche the world's fastest money making machine. In carrying out that mission,

he briefly attained supersonic speeds -- but then flew off the track,

culminating in his resignation from the firm last year.

Coming Full Circle

Porsche gambled away its independence and isnow being

taken over by VW. The merger may also mean a better chance for Porsche to find

its way back to its old passion for motor sports. Volkswagen heads Ferdinand

Piëch and Martin Winterkorn are both emotion-driven managers with a great love

for their products, and they are the ones who will now hold the decision-making

reins at Porsche as well. The two men have developed a strategy that will see

Porsche make a showing again at international auto racing's major arenas, for

example at the renowned 24 Hours of Le Mans race.

This means coming full circle for Piëch, now 72 years old. As

a young design engineer, he was responsible for developing the Porsche 917, a

brand legend that took the overall victory at Le Mans in 1970, burning through

significant amounts of money to do so.

Ferry Porsche, Piëch's uncle, later decided not to turn over

management of the company to any family member. He feared the firm could win

every race and yet still "end up bankrupt."

"Ferdinand Piëch didn't understand that decision then

either," Porsche noted in his autobiography.