while the refining industry in the Mediterranean, avoiding economic risk, preferred short-term upgrades to long-term investments. The uncertainty of the times and the geopolitical turmoil in the Middle East reinforced this caution and left the field open for massive EU subsidies for photovoltaics and wind turbines, disregarding the need for a balanced energy mix.

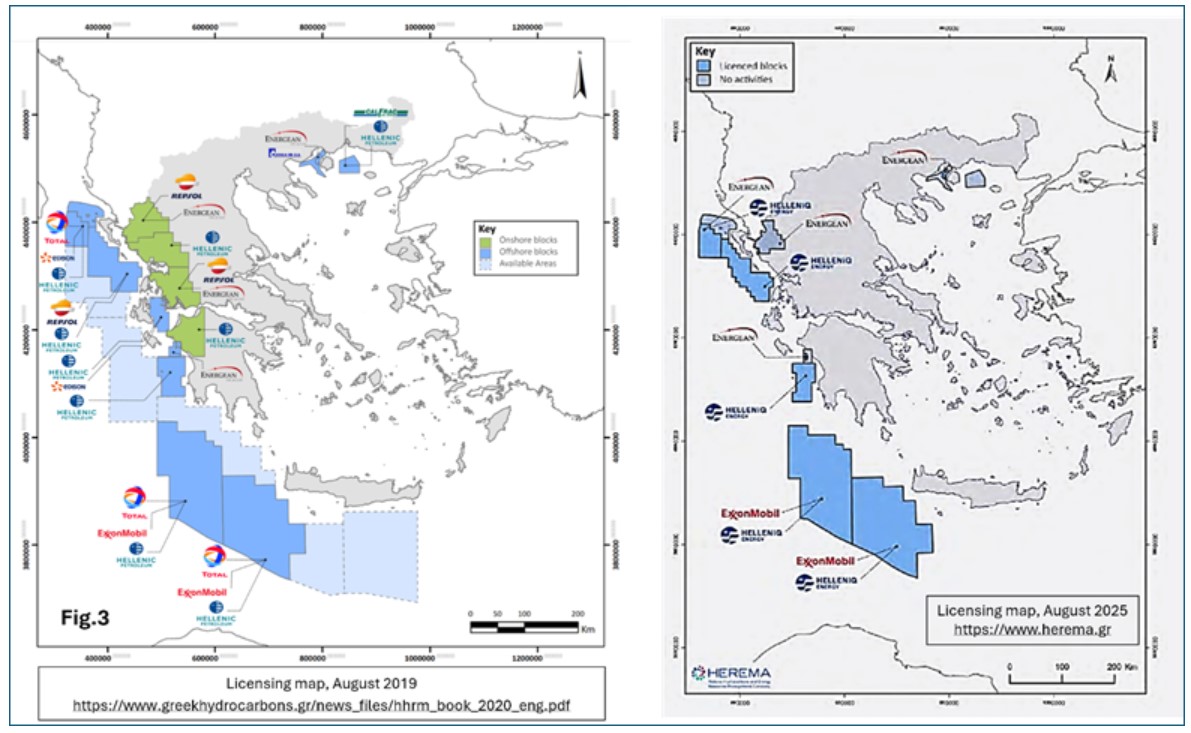

In 2019, Greece had thirteen offshore and onshore concessions, including oil production in northeastern Greece. This was the first time that the number of active concessions had been so high, with contractors including major oil companies from Europe and the US, under the supervision and coordination of the Hellenic Hydrocarbon Resources Management Company.

From 2020, the freezing of tenders south of Crete, the withdrawal of European companies Total and Repsol, and the withdrawal of Helleniq from many onshore and offshore projects have led to a drastic reduction in concessions, from thirteen to essentially five, due to the lack of suitable port infrastructure, environmental objections, geopolitical issues, and investment difficulties. However, this was a period of generous European subsidies and loans for the installation of large photovoltaic and wind power plants and the fast phasing out of lignite, foreshadowing the overproduction of electricity and curtailments at certain times, with no possibility of sale or storage of electricity. Meanwhile, pipeline imports of natural gas were increasingly supplanted by costly liquefied natural gas shipped by sea. This shift in energy policy, while aligned with climate goals, created imbalances in the national energy strategy. The lack of storage infrastructure and grid flexibility meant that renewable energy, despite its growth, could not fully meet demand or stabilize supply. Meanwhile, the retreat from domestic hydrocarbon exploration reduced Greece’s ability to diversify its energy sources and weakened its negotiating position in regional energy partnerships.

To heal these delays, a renewed focus on balanced energy planning is needed, one that integrates the strategic hydrocarbon development with renewables, improves infrastructure, and fosters public understanding of energy issues beyond ideological divides. Rebuilding investor confidence, accelerating regulatory processes, and enhancing cooperation with neighboring countries could help Greece reclaim its role as both a producer and connector in the evolving energy landscape of the Mediterranean.

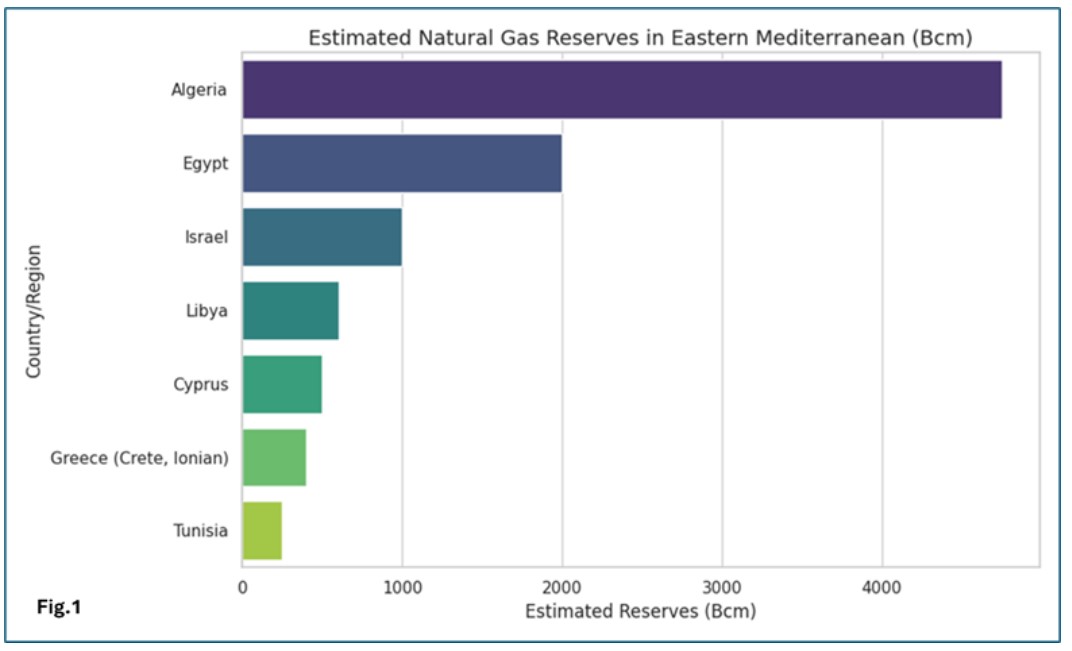

Natural gas reserves in the Southeastern Mediterranean and North Africa

The confirmed natural gas reserves in the Mediterranean region represent at least 1.7% of the world’s total proven reserves, amounting to approximately 3,500 billion cubic meters (Bcm) out of a global estimate of 206,000 Bcm. In Israel, the Tamar and Leviathan fields contain an estimated 1,000 Bcm of exploitable reserves, positioning the country as a significant contributor to regional energy resources. Cyprus has confirmed natural gas reserves in the Aphrodite, Glaucus, and Calypso fields, collectively estimated between 400 and 600 Bcm. The recent Pelopidas discovery is considered promising, though reserve volumes have yet to be disclosed. These fields are central to Cyprus’s growing role in the Eastern Mediterranean energy landscape, with export plans targeting Egypt’s LNG infrastructure. Egypt stands out with its Zohr and Noor fields, which together hold approximately 2,000 Bcm of recoverable gas. The Zohr field alone is considered to contain around 850 Bcm, making it one of the largest discoveries in the Mediterranean and reinforcing Egypt’s status as a regional energy hub. Although Greece remains in the exploratory phase, the renewed interest from major energy companies such as ExxonMobil and Chevron underscores its significant potential. Conservative estimates indicate that the regions surrounding Crete and the Ionian Sea may hold at least 600 to 680 Bcm of recoverable natural gas reserves. Lebanon also possesses offshore natural gas potential, but exploration efforts remain in their infancy due to ongoing geopolitical challenges that hinder development and investment. Palestine’s offshore Gaza Marine field, discovered in 2000, is estimated to contain 28 Bcm, though political constraints have prevented exploitation. According to the U.S. Geological Survey, the broader Eastern Mediterranean region may hold up to 300 trillion cubic feet (Tcf) of natural gas, equivalent to roughly 8,500 Bcm. Despite this vast theoretical potential, current estimates of recoverable reserves are more modest, ranging between 3,500 and 4,500 Bcm. In practical terms, this means that only about 50% of the estimated reserves in the Southeastern Mediterranean are currently considered extractable, highlighting both the promise and the limitations of the region’s energy future. Further west in North Africa, Libya possesses confirmed natural gas reserves of around 600 Bcm and exhibits promising signs of emerging offshore potential. Algeria, with confirmed reserves of around 4,750 Bcm, still has vast untapped onshore and offshore resources, supported by a well-established LNG export infrastructure. Tunisia’s estimated reserves stand at about 250 Bcm, while Morocco’s are more modest, ranging between 10 and 15 Bcm. Considering both commercial viability and geopolitical dynamics, the larger region’s total recoverable gas reserves are estimated to range between 8,500 and 10,000 Bcm (Fig. 1).

Rediscovering Potential: Greece’s Return to the Energy Map of the Mediterranean

In 2019, the Hellenic Hydrocarbon Resources Management state company estimated that the potential natural gas reserves from 30 exploration targets located west, southwest, and south of Crete, as well as in the Ionian Sea, range between 70 and 90 trillion cubic feet (Tcf). This corresponds to approximately 1,980 to 2,550 Bcm, or 12 to 15 billion barrels of oil equivalent (Bbloe). In addition to natural gas, the estimated crude oil reserves in the Ionian Sea and the onshore areas of western Greece are projected to reach 2 billion barrels, a volume of considerable economic significance for the country. Even if only 20% of the upper estimate, which is around 500 Bcm of natural gas, is commercially exploited, the impact could be transformative. By 2035, such development could substantially improve Greece’s trade balance, enabling the country not only to meet more of its domestic energy needs but also to export hydrocarbons. This would mark a strategic shift, helping to redefine Greece’s role from a transit corridor for foreign energy resources to an active energy-producing nation.

Undoubtedly, the natural gas deposits located near Crete and in the Ionian Sea enhance Greece’s role as an energy-producing country, moving it beyond its traditional position as a transit hub for foreign energy resources. These reserves offer strategic value and economic potential, but they also introduce new challenges. Their discovery intensifies regional competition and could strain existing partnerships between Greece, Cyprus, Israel, and Egypt, which have been cooperating on energy development in the Eastern Mediterranean.

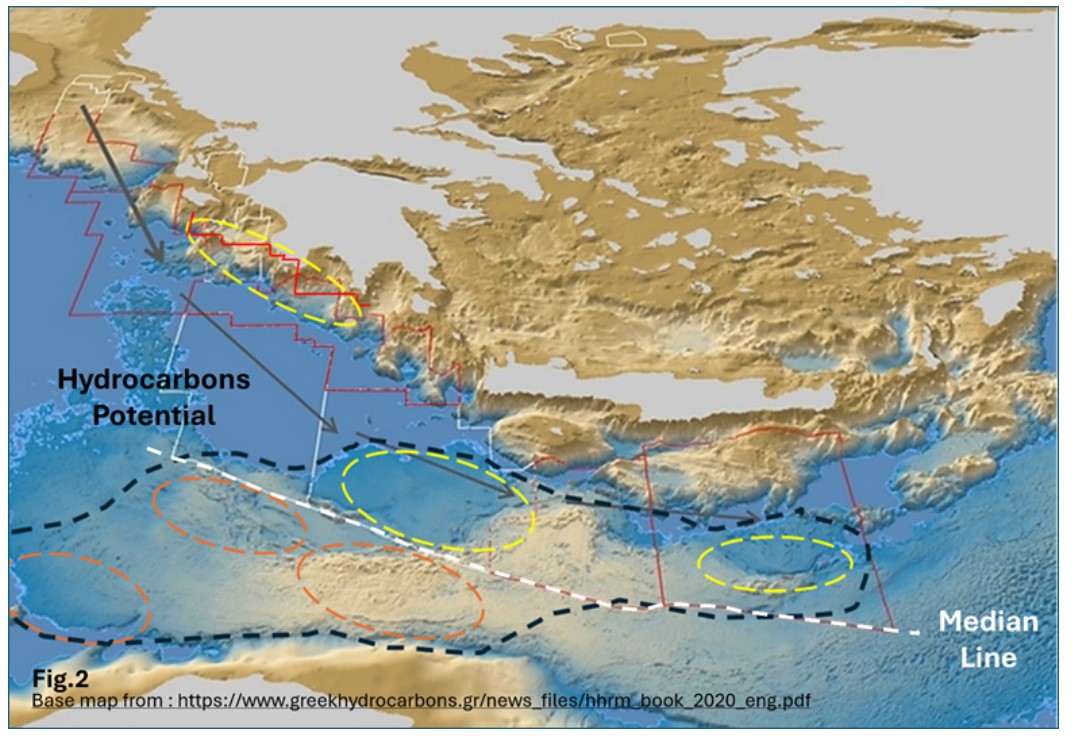

According to submarine geomorphology studies and the established maritime boundaries between Greece and Libya, Greek territorial waters play a key role in reinforcing the strategic importance of the area. The map of the seabed depth (Fig. 2) clearly illustrates how these geological and legal factors support Greece’s emerging energy profile. It is important to highlight that both Greece and Libya could contribute significantly to natural gas production on either side of the legally defined Median Line between them. This cooperation has the potential to extend the southeastern Mediterranean’s hydrocarbon reserves further west. If fully realized, this expansion could raise the region’s share of global proven natural gas reserves above 5%.

Summarizing, Greece’s geographical position in the southeastern Mediterranean gives it a key role in energy connectivity between North Africa and Europe. Its territory serves as a natural bridge for transporting energy resources, especially natural gas, across regions. This strategic location supports the expansion of energy flows and infrastructure, making Greece an essential part of regional energy networks and future supply routes.

Unlocking the Ionian and Cretan Blocks

The dilemma for Greece is not only how to exploit these potential reserves, but how to convert its energy potential into political influence and economic prosperity. A realistic drilling schedule for Greece should prioritize the initiation of exploration activities west and southwest of Crete, as well as in the Ionian Sea, before 2027. This timeline aligns with existing contractual obligations and European safety regulations. It also serves to preempt potential opposition framed as environmental concerns, objections that often coincide with broader geopolitical tensions in the region.

The areas south of Crete and southwest of the Peloponnese remain strong candidates for subsequent phases of exploration. However, progress in these zones has been slower, as the tendering processes have not yet been finalized (Fig. 3). Accelerating these procedures will be essential for maintaining momentum and securing Greece’s strategic position in the regional energy landscape.

A Tentative Comeback: The EastMed Pipeline’s New Chance in a Shifting Energy Landscape

The EastMed pipeline has re-emerged on Greece’s strategic agenda for the third time, aiming to reinforce the positions of both Greece and Cyprus amid increasing external pressures. Its advancement, however, depends on several critical factors. High-level intergovernmental agreements are essential to ensure political alignment and regional cooperation. Public support and regulatory preparedness are equally important, as the project must navigate environmental concerns and legal frameworks. Moreover, the long-term commitment of the European Union will be vital, both in terms of political backing and financial investment. Robust technical planning and engineering expertise are also required to address the pipeline’s complex construction and operational demands. The finalization of the pipeline’s design and the securing of financing will be decisive steps. If these are achieved, the construction phase could begin, with the pipeline expected to become operational sometime after 2030 (Fig. 4).

If the European Union continues to prioritize the diversification of its energy sources, the EastMed pipeline could be financed as a strategic infrastructure project. For the pipeline to move forward, however, a substantial increase in the volume of exploitable reserves across the southeastern Mediterranean is essential and drilling efforts in Greece must yield commercially viable results. Yet, several challenges threaten the economic viability of a new pipeline. The present reserves of the southeastern Mediterranean already play a vital role in supporting Egypt’s economy and supplying energy to Israel and Jordan. Egypt is experiencing a decline in production from its existing reserves, while its subsea pipeline infrastructure has unused capacity and its export terminals are operating below full potential. These factors underscore the urgent need to boost regional output to justify the cost and scale of a new pipeline project. Complicating matters further, a recent agreement to increase Israeli natural gas exports to Egypt via existing pipelines is expected to reduce the volume of gas available for alternative routes such as a new pipeline to Crete and onward to the European market.

Considering these constraints, liquefied natural gas (LNG) infrastructure may emerge as a more practical alternative. LNG terminals for liquefaction and regasification are technically mature and capable of meeting immediate energy demands with greater flexibility. However, while LNG offers short-term advantages, it also introduces new vulnerabilities. It increases dependence on external markets, exposes supply to volatile spot prices, and ties energy security to global fluctuations, ultimately undermining the original goal of regional energy security.

Strategic Outlook

In conclusion, the Eastern Mediterranean is rapidly evolving into a key energy hub for the 21st century. Crete and the Ionian Sea, due to their strategic location and promising geological indicators, have the potential to become complementary energy corridors linking North Africa with Europe. This western axis is particularly significant, as it strengthens both the security of energy supply and geopolitical cohesion across the region. North Africa, especially Egypt, Algeria, and Libya, remains a cornerstone of the EU’s energy strategy. In this context, enhancing the interconnection between the Eastern and Western Mediterranean is not just a technical ambition but a geopolitical imperative. Realizing this vision will require a coordinated strategy, sustained political will, and a clear commitment to embedding energy development into Greece’s broader national and regional agenda.

* Yannis Bassias served as President and CEO of the Hellenic Hydrocarbons Management State Company from 2016 to 2020. He was a member of the Committee of the National Energy and Climate Plan (NECP) from 2018 to 2020 and collaborated with municipalities in Western Macedonia on the development of energy and mineral resources. He has extensive experience in the international hydrocarbon industry and energy mix issues. He regularly writes and analyzes energy topics related to European energy policy in both Greek and international press.

(source moderndiplomacy.eu)